1. Edward T. Hall (1914-2009) is widely considered the father of intercultural communication. He developed the popular concept of high and low context cultures and wrote numerous books about the field.

2. Geert Hofstede is a researcher whose groundbreaking theory of cultural dimensions laid the foundation for future cultural research.

3. Fons Trompenaars is a cross-cultural communication scholar and prolific author. Along with Charles Hampden-Turner, he built on Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory.

4. Stella Ting-Toomey is a researcher and Professor of Communications at California State University, Fullerton. A successful author in her own right, her numerous contributions to books and journals are at the core of the intercultural communication curriculum.

5. William B. Gudykunst (1947-2005) was a communications scholar, author and researcher whose vast body of publications are still relevant to the field today.

6. Milton J. Bennett is the co-founder of the Intercultural Communication Institute (ICI), a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting cultural understanding and one of the premier resources of all things intercultural. Bennett is also (or has been) a researcher, lecturer, author and intercultural trainer.

7. Janet M. Bennett is the co-founder of the Intercultural Communication Institute and now serves as executive director. The ICI sponsors the annual Summer Institute for Intercultural Communication which is three weeks of workshops dedicated entirely to the intercultural field and surrounding issues. Bennett is also very active in numerous capacities throughout the intercultural field.

8. Richard D. Lewis is a linguist, author and founder of Richard Lewis Communications. His innovative book, When Cultures Collide, has met with great success. He also designed The Lewis Model of Culture as a guide to classifying cultures. Follow his blog here.

9. Young Yun Kim is a professor of Communication at the University of Oklahoma, Norman. She is known for her Integrative Communication Theory and has also published numerous works in the field.

10. Fred E. Jandt has authored several textbooks on intercultural communication and is Dean and Professor of Communication at CSU San Bernardino.

Top 10 Intercultural Communication Scholars

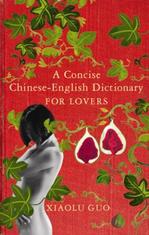

Tuesday, 20 December 2011A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers

Wednesday, 11 May 2011I just finished reading this book: A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers by Xiaolu Guo. Here’s the synopsis:

Twenty-three-year-old Zhuang, the daughter of shoe factory owners in rural China, has come to London to study English. She calls herself Z because English people can’t pronounce her name, but she’s no better at their language. Set loose to find her way through a confusion of cultural gaffes and grammatical mishaps, she winds up lodging with a Chinese family and thinks she might as well not have left home. But then she meets an English man who changes everything. From the moment he smiles at her, she enters a new world of sex, freedom, and self-discovery. But she also realizes that, in the West, “love” does not always mean the same as in China, and that you can learn all the words in the English language and still not understand your lover.

Drawing on her diaries from when she first arrived in the UK, Xiaolu Guo winningly writes the story in steadily improving English grammar and vocabulary. Freshly humorous, sexy, and poignant, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers is an utterly original novel about language, identity, and the cultural divide.

While this book is fiction, it is jam-packed with observations about British versus Chinese culture and the English and Chinese languages. One passage that resonated with me was this:

I am sick of speaking English like this. I am sick of writing English like this. I feel as if I am being tied up, as if I am living in a prison. I am scared that I have become a person who is always very aware of talking, speaking, and I have become a person without confidence, because I can’t be me. I have become so small, so tiny, while the English culture surrounding me becomes enormous. It swallows me, and it rapes me. I wish I could just go back to my own language now. But is my own native language simple enough? I still remember the pain of studying Chinese characters when I was a child at school.

Why do we have to study languages? Why do we have to force ourselves to communicate with people? Why is the process of communication so troubled and so painful?

Have you ever experienced this? Do you have answers to the questions she poses? Have you read the book?

Learning English through Film

Wednesday, 4 May 2011Many people credit watching films and television with helping them to learn a foreign language. While this is definitely feasible, catchphrases from popular films can also help those learning English or trying to assimilate to live in the United States.

How many times have you heard yourself say “I’ll be back” when departing from a friend?

What about “we’re not in Kansas anymore” when traveling or experiencing something new and different?

Have you ever introduced yourself jokingly using your last name first as in “Bond, James Bond”?

I’ve strung together three things on more than one occasion à la “lions and tigers and bears, oh my”!

Do you know which films these are from? Do these turns of phrase really have any significant meaning? Would you understand them if someone said them to you?

Our speech is peppered with words and phrases like these which non-native speakers might be baffled by. But making a concerted effort to learn some of these, incorporate them into your vocabulary or, at the very least, understand what they mean can have a positive impact on one’s language experience.

Which film catchphrases do you find yourself using? Are there any you don’t understand? Have you ever had a positive or negative experience where a lack of understanding inhibited communication?

10 Things I Never Did Until I Lived in Russia (Part 3)

Tuesday, 3 May 2011The third installment, continued from here:

1. Had people not know where I was from. In the United States it’s common to ask people where they are from and then form an opinion about them based on their answer. I’m originally from Ohio and though I don’t come from a small town I constantly heard jokes about how I grew up on a farm. But in Russia no one knew where Ohio was or what it meant to come from there or what the local stereotypes were. I wasn’t an Ohioan, I was an American.

2. Accepted cheating as a normal form of behaviour. In this context I’m talking about students cheating on tests although I’ve heard that cheating in relationships is also quite common. As a teacher I was told to expect my students to cheat and this was part of the culture. They weren’t cheating, they were helping their friends. The first time I saw students blatantly cheating, I was shocked. But as time went by I got used to it and came to expect it.

3. Washed my hands every time I came home. This may sound gross, but I really don’t remember washing my hands that much before I came to Russia. For some reason this happens a lot here and now it’s somewhat of a joke. I think it’s because many things are so dirty in public and when you come home you feel a layer of grime on your skin that begs to be washed. This habit has carried over now that I’m back in the US and now I always wash my hands when I get home.

4. Bought milk in a bag. For some reason this was one of the things I constantly found amusing as it made no sense to me. How do people use this product? Some bags had nozzles that could be re-capped but others didn’t. Do people pour milk into a separate container or drink the entire bag in one sitting? So baffling!

4. Bought milk in a bag. For some reason this was one of the things I constantly found amusing as it made no sense to me. How do people use this product? Some bags had nozzles that could be re-capped but others didn’t. Do people pour milk into a separate container or drink the entire bag in one sitting? So baffling!

5. Was pestered about being single. I went to Russia straight out of university where no one ever bothered to ask if I had a boyfriend or was married. But in Russia it’s common to marry quite young and I knew people younger than myself who were married and/or had a child already. My boss often asked me if I was in a relationship and thought I should be in one lest I become lonely. My students sometimes couldn’t believe I wasn’t married and had no desire to marry in the immediate future.

6. Had two front doors. No, there weren’t two separate entrances to my flat. There was one entrance with two doors. There’s a lovely picture here. So strange and I don’t know if it was for security reasons or maybe to keep heat inside the flat.

7. Wasn’t asked for identification anywhere. If I went to a club or restaurant, ordered or bought alcohol, I was never once asked for identification. The drinking age in Russia is 18 and I do look that age, but compared to the strict rules in the US where anyone under 30 is asked for identification, this was a nice surprise. Now that I’m in the US again I often forget to bring my ID and have been refused service numerous times because of this.

8. Ate caviar when it wasn’t a special occasion. Many people associate caviar with Russia but also with special occasions. It’s often thought that eating caviar and drinking champagne (or vodka) is the height of sophistication. But in Russia caviar can be eaten any time and is often served on pancakes (blini) or on bread with butter.

9. Had people rave about home cooked food. I love to cook, especially desserts. Many Russians cook meals but cakes and other sweets are primarily bought. When I made chocolate cheesecake or other desserts my Russian friends couldn’t believe I made it myself and said it was the best they’d ever tasted.

10. Had to remember to bring toilet paper to the restroom. Although most WCs now have toilet paper inside the individual stalls you will find, on occasion, a restroom where there is one main roll of TP in the central area of the bathroom. This happened to me several times when I was a student in St. Petersburg. I’d enter the bathroom, walk straight to a stall and then realize there was no toilet paper.

Is Your Writing Giving You Away?

Wednesday, 2 March 2011Do you know how to write in another language? Sometimes just learning the alphabet or characters and how to spell the words isn’t enough. Some languages have small differences that one might not take into account when first writing in another language.

In Russian, handwriting is written at an angle instead of vertically like English. The picture above illustrates standard paper for children to learn their handwriting. Children who are learning to write Russian use paper with slants on it to train them to write at an angle. Often when I write Russian I write the characters, looping them together perfectly (another difference between cursive English and cursive Russian) but mine often stand straight up and down.

Anyone who knows about the Russian slant would immediately know I were a foreigner just by reading my writing, no matter who perfect my spelling or grammar. Other languages have more noticeable differences. Some languages are written left to right or even vertically. As an English speaker I am not conscious of the fact that I’m writing right to left, it’s second nature to me.

What other differences could there be in languages that we never pay attention to?

To Curse or Not to Curse?

Monday, 14 February 2011One of the first things many language learners enjoy discovering when learning a language is all the bad words. While this can undoubtedly be entertaining, knowing bad words in a language can also be useful. Knowing when someone is cursing at you is important if you want to avoid confrontational or even dangerous situations. Knowing when to use an appropriately strong and effective word can also make a point when necessary.

But just because you know how to curse in a language, does that mean that you should? A recent article states that cleaning up your language can contribute to one’s professional success as well as make the world a better place.

While living in Russia the decision of whether or not to curse was one that I found myself contemplating. I quickly learned numerous bad words in Russian and how to use them in everyday conversation. But I also realized that there’s somewhat of a taboo against women using foul language. Most of the bad words I heard were used by men and when I tried to speak using such words some people admonished me. While I thought incorporating bad language was a part of learning the language and speaking like a native speaker, apparently some words aren’t acceptable even if other people use them.

Although I can’t say there were any negative repercussions because I used the words sparingly and among friends, I can see the potential for the use of bad words to cause problems. So, when in doubt, no matter what language you speak, don’t use bad words. It’s not a bad idea, though, to educate yourself about this aspect of a language so you can understand what others are saying or to know which words to avoid.

What experiences have you had learning bad words in another language? In your culture is it acceptable for some people to curse and not others?

A Fine Line Between Respect and Insult

Tuesday, 1 February 2011Many people agree that when visiting another country you are a guest and should try to respect the rules of your host country. This means observing the customs there, trying to speak the language, and trying to understand the people. But is it possible to go too far when trying to show respect? When can attempts at respect cross the line into insulting?

The premise for this post came from something I read that said it is insulting to members of the Arab culture for foreigners to wear traditional clothes. At first this may seem contradictory because a foreign visitor may think that wearing traditional clothes is a way to show respect for the culture and be modest. After all, tourists are known to get in trouble when visiting Arab countries by dressing immodestly.

But where do you draw the line between showing respect and covering up by wearing modest clothes and wearing traditional garments that belong to a culture of which you are not a part?

Now I can’t recall where I read this and I haven’t been able to find any sources to include in this article. If anyone can confirm or deny this, I’d be happy to learn more about the topic.

But most importantly I thought it raised a very important point. While it is very important to learn about a culture and respect its ways, you should also be informed enough not to insult that culture by going too far.

Have you had an experience like this? What other examples of taking cultural respect too far can you think of? Is the example of Arab clothing really true?

10 Things I Never Did Until I Lived in Russia (Part 2)

Thursday, 23 December 2010Continuing from my previous list, here are 10 more things I never did until I lived in Russia:

1) Didn’t sleep in a “real” bed. Due to the small size of many Russian flats, space is limited and furniture sometimes performs double functions. The most common is that of the sofa bed. I found that many people didn’t sleep in what I would call a “real” bed. Instead they slept on a sofa, futon, or other bed-like piece of furniture. This didn’t present any problems until I moved into a new flat, decided to buy a bed and was met with incredulity. Some people couldn’t understand why it was important for me to have a bed. But when given a choice between a bed and a sofa, I chose the bed.

2) Read cheesy books. The selection of books available in English in Russia is often quite limited, even in big bookstores like Dom Knigi and Biblio-Globus. This meant that sometimes when I was so desperate to read something in English, I ended up reading books that I can only describe as cheesy. Books that I would never read if I was in the United States and had more variety. But sometimes you just need to read a book in English!

3) Saw my coworkers and boss naked. See my previous post on nudity.

4) Ate at McDonald’s. I don’t if there are any significant differences between McDonald’s in the United States and the ones in Russia but, in my opinion, the food at the ones in Russia tastes better. It seems to have more flavor and is not as greasy or sickening. I don’t eat McDonald’s when I’m in the US but doing so didn’t seem quite so bad while living in Russia. Maybe it wasn’t even healthier, but it definitely tasted better and also gave a level of comfort and familiarity, despite the small differences in taste.

5) Knew Russian celebrities. When I was studying Russian as a university student, I was oblivious to a lot of Russian popular culture. My professor played several popular films and songs in class so I was aware of a few things. But while living in Russia, I quickly absorbed knowledge of popular films, who the actors, actresses and TV personalities were and other random knowledge. Knowing about these things was also helpful in order to feel a part of the conversation, to understand jokes and make cultural references.

6) Drank tea. Like most people, I’d always associated tea with England. I had no idea that Russians drank so much tea. While I rarely drank tea on my own, it was something of a social activity at work and I soon found myself mindlessly drinking cup after cup of tea throughout the work day. At home I never drank tea but always kept some on hand in case I had Russian friends visiting.

7) Drank sparkling water. Before I came to Russia I enjoyed drinking sparkling water but it wasn’t something I did that often. It’s not standard in the United States and can be difficult to find in shops and restaurants. But in Russia it’s almost the norm. When ordering water at a restaurant or from a street vendor, it’s important to verify whether you want it to be sparking (with gas: с газом) or still (without gas: без газа). Sparkling water is also the same price as still and is relatively cheap. Consequently I ended up drinking copious amounts of it and came to enjoy it even more than before.

8) Took a gypsy cab. In Russia there are official taxi cabs and then there are gypsy cabs: cars that ordinary people drive but are willing to offer you a lift for a price. I never took them alone but, when traveling with friends, sometimes found myself in some random person’s car. It was an interesting experience that while shocking at first, soon became the norm for transportation when taxis weren’t available.

9) Drank straight vodka shots. Many are aware of the connection between Russia and vodka. Before living in Russia, I rarely took a shot of straight vodka. If I did, it was at a party or club with the sole intent of becoming drunk. But in Russia I found myself taking shots at lunch or dinner and was told not to sip but to swallow the whole shot.

10) Had people be surprised I was skinny. In the United States most people expect you to be a certain size. Your body is only commented on when it is either too big or too small. Americans are known to be obese and Russians are aware of this. I’ve always been petite but no one said anything about it until I lived in Russia. One woman was surprised to find that I was American and said, “But you’re not fat!” She seemed genuinely shocked as if being fat were a requirement for being an American.

Cultural Nationality vs. Nationality and Citizenship

Wednesday, 22 December 2010One of my best friends was born in Russia but came to the United States at a very young age. She was raised in the United States, speaks English like a native speaker, attended and graduated from both American school and university and is now married to an American. She celebrates Thanksgiving, Christmas and all the other US holidays. The only thing about her that isn’t American is her passport: her citizenship.

According to this definition, both her nationality and her citizenship are Russian. But what about her cultural nationality? If you were to meet her on the street, you would think she is American. She studied Russian at university and understands quite a bit more about Russia than the average American. But if she were to go to Russia, she would more than likely be recognized as a foreigner, no matter what her passport says.

Now my friend has a younger sister who is about to finish university. She’s in almost the exact same situation. She holds a Russian passport but that’s where her ties to Russia ends. She doesn’t speak Russian and, to my knowledge, has never studied anything Russian culture and considers herself an American. Her cultural nationality is American.

While visiting my friend we began discussing her sister’s situation. While she’s a student, she is allowed to remain in the United States. But unless she continues to graduate school, finds a job and gets a work visa, or marries, she may have to return to Russia.

I’m not aware of all the details of her situation but I can’t even begin to imagine what it must be like. For her, her cultural nationality is American. She has no ties to another country. What would it be like for her if she had to return “home” to a place that she may not even have a memory of? What would you do if your entire experience was of another country and then had to return to a place where you didn’t speak the language or understand the culture?

So I started thinking of cultural nationality. No matter what your passport says or where your citizenship lies, cultural nationality is a strong force. It’s also possible for the opposite situation to be true. For example, someone immigrates to the United States, becomes a US citizen, but their cultural nationality still belongs to their home country. No matter where they live, they haven’t adapted to the new culture and don’t feel like this is their home.

Is cultural nationality valid? Can one indeed belong to one nationality but have a different cultural nationality, no matter what their citizenship? Should cultural nationality be taken into account when deciding upon cases like my friend’s sister? Should she be granted citizenship because she is practically an American citizen?

The Appeal of the Expatriate Lifestyle

Tuesday, 21 December 2010People become expats for a wide variety of reasons. Some do it for financial reasons, others have a thirst for adventure and some have no choice when their jobs call for them to move around the globe.

While living in Russia, I met a lot of expats who didn’t move abroad for work or to be with a boyfriend or girlfriend. Many had originally planned to stay for a year just to have a bit of adventure, and ended up staying a lot longer. I also noticed that many of them were not very integrated into Russian culture, didn’t have a lot Russian friends and spoke hardly any Russian at all. They preferred the company of other expats. So why did they stay? What was the appeal of living abroad? As I contemplated these questions, I generated a list of possible perks:

1) Living abroad gives you a sense of uniqueness. Many of the people I met were the only person in their family who had ever been or lived abroad. Those who came from small towns seemed to look upon living abroad as a badge of honor. There were a bit sophisticated and interesting because of their international experience. There’s also an element of uniqueness to your nationality. In small towns you may be the first and only American some people have ever met. Many Russians, for example, enjoyed meeting Americans and Brits and so you became instantly interesting based not on your own personality, but on your nationality.

2) No one knows where you’re from. While many people might know which country you are from, few will know which state (if you’re from the United States) or city you were born in. Of course, other people from your home country will know, but others around you will probably have different ideas. Many of the Russians I met had no idea where I was from. Even if I pointed out my city on a map, they didn’t have any frame of reference for the place I indicated. Other Americans, however, would tease me from time to time about where I was born. I had no idea of where the British people were from and couldn’t make judgments based on their accents or education like other Brits could.

3) You don’t have to follow all the rules. If you live abroad and don’t know the cultural rules, more often than not you’re given a cultural pass because you’re a foreigner. Of course there are limits to this. But I noticed that many people would notice a cultural faux pas made by a foreigner and brush it off, saying to themselves, “Well, he/she is American.”

What other factors make being an expat appealing? Have you or someone you know experienced any of these?

Uncategorized |

Uncategorized |

Posted by JMS

Posted by JMS